Horse Racing - Picking Winners - Part 2

Part 3

7 Criterion 1 - Five Furlong Sprint Handicaps

8 Criterion 2 - Six Furlong Handicaps

9 Criterion 3 - Two-mile Plus Handicaps

10 Criterion 4 - Form Figures In All Handicaps

11 Criterion 5 - Maiden Winners First Time In A Handicap

13 Non-Handicaps - Backing And Opposing Favourites

14 Criterion 7 - Group One/Two Races For Three-year Olds And Over

6 Instant Handicapping

Last-time-out form in relation to weight and grade should be the main focus of the conventional form reader, possibly combined with an appreciation of the longer view of each horse's chance reflected in race ratings based on a private handicap. Look for very good recent form and a high, if not the highest, race rating.

An alternative approach is possible, however. It is based on general, statistical data drawn from the form book and has the advantage of finding favoured horses quickly and automatically, without the backer having to judge the niceties of form. Unique to this article, it has been given the name of instant handicapping.

Instant handicapping is not some miraculous oracle. It will not pick the winner of every handicap. If every single horse indicated by it were backed to win, it would probably not produce a level- stakes profit over an extended period, but what it will do is show readers how to choose a great many winners of hank reap niece, probably a lot more than they have ever been able to pick before.

The method is based on a basic racing truth: class tells in handicaps as much as in any other horse race. Or, horses near the top of the weights win much more often than those at the bottom. this trend is so pronounced that with the aid of a few simple rules it can be converted into a point at which bookmakers, for all their careful regulation of the odds, may be vulnerable.

Instant handicapping was developed many years ago from a large amount of data which is, inevitably, now dated but which has served well ever since. For the purposes of this article, however, and as a way of reaffirming the statistical validity of the principles behind the method, another much smaller survey was undertaken in which the results of 100 Flat handicaps were recorded before being arranged into a meaningful pattern.

May was chosen for the survey. The new Flat season is about five weeks old at the beginning of the month and form has settled down to a great extent. Trainers are still keen to get races into every one of their charges and fields are definitely large compared with later in the year. This is the ideal scenario for demonstrating the ideas which underpin our instant handicapping methodology.

The point about the sample of handicap winners set out below is that it is purely random. Once the process of recording results on a daily basis was begun, no winner was omitted, whatever its price or position in the handicap, until the 100-race mark was reached.

The largest field in the block of results was one of 29 runners, and the smallest six, but the vast majority of the 100 races had more than 10 runners, often many more. Because in many of the handicaps one or more horses are set to carry an identical weight, it was convenient to assign the positions in the handicap a letter rather than a number — thus avoiding the confusing use of equals signs — where A is always the top weight, B the second horse down in the weights, C the third, and so on. Overweight and the allowance for apprentice jockeys were completely ignored.

The preceding table reveals some highly significant points which ought to be the subject of further analysis. The quite high number of wins recorded by K, M and in particular by O, where some big prices would have yielded a good level-stakes profit, are almost certainly something of an aberration, and would probably not be repeated in another survey. More likely some other letter or letters would have an exceptional run of good fortune but, although the sample of 100 races is small enough to allow for this kind of luck to play a part, nevertheless there is a clear, and to some extent predictable, pattern in the figure as a whole.

If the general proposition that high weights in handicaps do best and bottom weights do worse is correct and that the weights in between win in approximate proportion to that model, then what you would expect to see is a triangle. With the exception of the two top weights, that is what you have.

Looking at the figure from the bottom up and from left to right, the hypotenuse of the triangle can be drawn in from the 12—1 of W to the 14—1 of D.

There is a very good reason to explain why the top two positions have done relatively badly. The handicapper who, according to the most uncharitable view, never forgets, tends to be hard on horses which show an exceptional run of form or even run just one exceptional race. Such horses rise rapidly to the head of the weights within their class. Their measure is taken and they are no longer capable of winning off their high rating. Once this has happened, a horse might remain too high in the weights for the rest of its racing career.

This is not an exceptional scenario. It is a situation which, to a greater or lesser degree, occurs all the time and certainly to the extent that any method of betting in handicaps needs to have built into it some device by which animals so afflicted are identified and excluded for betting purposes.

Leaving refinements apart for the moment, it is clear from the figure that the four positions C to F are the best consecutive positions and it is around this area that the vulnerable point for the bookmaker occurs. If there had been an equal distribution of recorded victories, the strike rate for weights would have been 100 x 4/23 = 17.39 per cent. The actual strike rate for the positions C to F is in fact much higher, at 40 per cent of the sample.

The author knows from other data, however, that there may be some element of lucky aberration in the F position. Since Our final methodology will not abandon the highest weights entirely, it is also worth noting that the five weights A to E produced a total of 43 per cent of the wins. Put another way, over two-fifths of all the handicaps in the survey were won by one of the top five in the weights.

It is also possible to draw some pretty definite, general conclusions about the starting prices of winners. Below are the 100 results arranged according to this factor, where the data has been put into bands of starting prices reflecting various levels of confidence within the racecourse betting market. Once again there appears to be an area where the bookmaker looks vulnerable to the backer who works from statistical record.

| Up to 2/1 | 5 winners |

|---|---|

| 9/4 to 4/1 | 14 winners |

| 9/2 to 15/2 | 39 winners |

| 8/1 to 10/1 | 9 winners |

| 11/1 to 14/1 | 17 winners |

| 16/1 to 20/1 | 12 winners |

| 22/1 or over | 4 winners |

The price range of 9/2 to 15/2 is outstanding with 39 per cent of all winners contained within it. The ranges 9/4 to 4/1 and 11/1 to 14/1 are roughly equal and both produce slightly more winners than 8*1 to 10/1. But, when it comes to choosing a favoured group of prices on which to concentrate, the very narrow 8/1 to 10/1 band added to 9/2 to 15/2 is surely best for the punter. Horses quoted 9/4 to 4/1 do not offer value in terms of likely profitability from a by-no-means-exceptional strike rate of winners; and 11/1 to 14/1 chances, though clearly more remunerative individually, are in fact very plentiful in any typical handicap with a fair number of runners. This would reduce the overall profitability from successes, and indeed, would probably result in an actual loss overall. Also, they are impossible to identify from newspaper forecasts, as they are usually included among the unspecified 'others'.

On the other hand, an unbroken price band from 9/2 right up to 10/1 inclusive offers the punter a readily identifiable, consecutive group of horses from within the normal betting forecast range. Even if on occasion some of them start and win at longer odds than 10/1 they would still fall into our net. The survey, derived solely from starting prices, showed a strike rate of 48% from the 9/2 to 10/1 band, or nearly half the races. This is definitely the odds range which should be the focus of the punter's attack on the bookmaker.

RULES

We are now in a position to lay down the rules of the instant handicapping method, which are as follows:

1 Concentrate on the top five horses in the handicap, including all horses set to carry equal fifth weight. Ignore apprentice allowances.

2 Strike out, however, any horse due to be ridden by a jockey claiming either seven or five pounds.

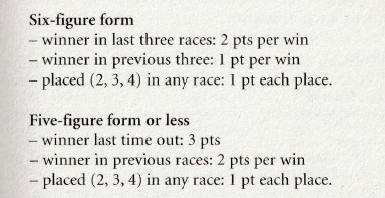

3 Rate the form figures of the two top weights in the race by these scales:

Strike Out any horse with a total Of less than 4 points from six-figure form, less than 3 points if it has only run five times in all, or less than 2 points if it has run four times or less.

4 Consider only horses quoted between 9/2 and 10/1 inclusive in the betting forecast of the newspaper you use for betting purposes.

Rule 3 imposes a minimum form qualification in order to eliminate those top-weighted no-hopers of which the handicapper has probably taken full measure, as well as those which find themselves at the top end of the handicap for technical reasons which have nothing to do with racing ability, such as failure to meet qualifying standards for a realistic weight.

Rule 2 eliminates horses ridden by very inexperienced apprentices. They are seldom value for the weight concession. Horses so ridden rarely win, for the presence of a 'chalk' jockey in the plate of a highly weighted runner is in fact a sure sign that a horse is 'not off' today.

It was gratifying to find that although there had been a considerable gap in time since the rules of instant handicapping were originally formulated, the survey of a block of recent results did not call for any modification in the rules. The instant handicapping method appears as good now as when it was created.

How often can you expect to win with it? We have already admitted that it is not a magic oracle, but the punter who turns to it as a selection method still has every right to expect some very good days. Several horses are often indicated in the same race. This is unavoidable and it is left to the reader to decide exactly how to use the instant handicapping method. You might make a choice based on your reading of form or you may prefer simply not to bet when the method indicates more than one horse. Or again, you might decide to back all the possibles in a race, dividing the stakes equally or regulating stakes more systematically as explained in Part 3.

At all events, instant handicapping is a viable alternative to conventional ways of assessing form in handicaps. Selections are fully automatic, no judgement is required on the part of the punter, and it is the work of a few minutes to check out the daily indications. If attracted to the method, one has every chance of finding many winners in the future.

On the other hand, we have said that specialisation pays the biggest dividends, and there now follows a series of criteria in which very specific guidelines are given for various types of race.